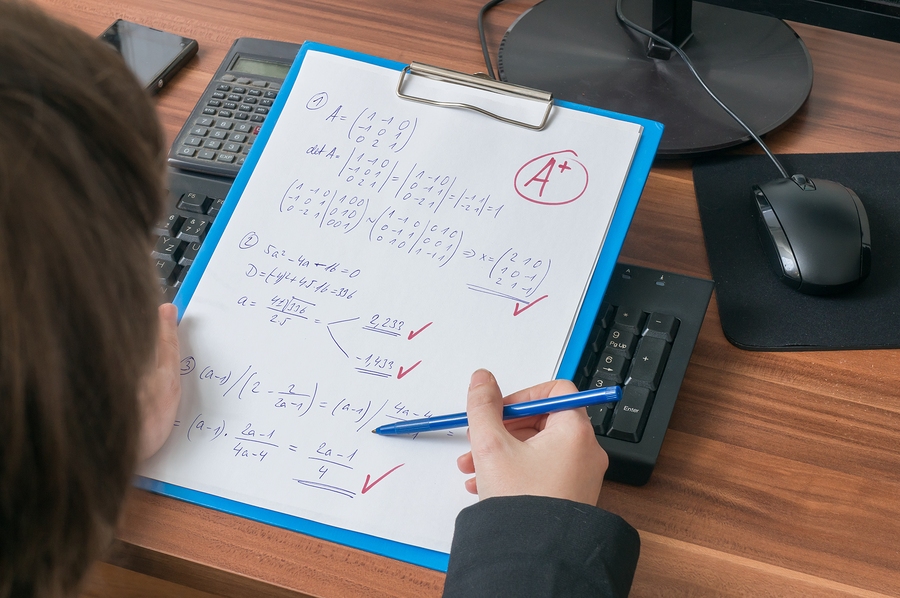

When everyone’s a winner, nobody’s a winner. And this is especially true when it comes to grade inflation, a decades-old nationwide trend to elevate grades for a certain amount of work. According to Rojestaczer and Healy, “it’s difficult to ascribe this rise in grades to increases in student achievement” (2) as their studies have shown entrance exam scores have not increased. Students are more disengaged from their studies and the literacy of graduates has declined. And yet grades continue to rise. With grade inflation, A’s are now average. Nobody stands out as a better candidate for employment or acceptance into graduate school. The trend, according to Magdelena Kay, an associate professor at the University of Victoria,“...is dishonest. It hides the truth of a student’s performance” (42). And I would say it serves to further the entitlement mentality in so many of our youths today. A superfluous reward cheapens the reward. It’s a slippery slope which is making grades meaningless and leading to the possibility of doing away with them altogether. Afterall, if they’ve lost their value, why use them at all?

When everyone’s a winner, nobody’s a winner. And this is especially true when it comes to grade inflation, a decades-old nationwide trend to elevate grades for a certain amount of work. According to Rojestaczer and Healy, “it’s difficult to ascribe this rise in grades to increases in student achievement” (2) as their studies have shown entrance exam scores have not increased. Students are more disengaged from their studies and the literacy of graduates has declined. And yet grades continue to rise. With grade inflation, A’s are now average. Nobody stands out as a better candidate for employment or acceptance into graduate school. The trend, according to Magdelena Kay, an associate professor at the University of Victoria,“...is dishonest. It hides the truth of a student’s performance” (42). And I would say it serves to further the entitlement mentality in so many of our youths today. A superfluous reward cheapens the reward. It’s a slippery slope which is making grades meaningless and leading to the possibility of doing away with them altogether. Afterall, if they’ve lost their value, why use them at all?

The Road to Hell is Paved With Good Intentions

It is said “the road to hell is paved with good intentions” and this seems quite appropriate when referring to grade inflation. Grade inflation was started, like many things, with good intentions. Stuart Rojstaczer, a former Duke University professor of geology, and Christopher Healy, an associate professor of computer science at Furman University, have put together a comprehensive study of college grading through the decades. Their findings show a rapid rise in grades in the 1960’s which correlates to the Vietnam War. This era was then followed by a period of static to falling grades (2). They have drawn the conclusion that professors were reluctant to give students D’s and F’s because poor grades meant young men would be flunked out of school only to be drafted into the war.

The end of Vietnam, however, did not put an end to grade inflation. The rise continued in the 1980’s. What was the factor then and beyond? One factor may be the work of Dr. Benjamin Spock, an American pediatrician well known for his parenting books. His works predated and paralleled the rise in grades. He greatly influenced and changed the way several generations of parents would parent their children. The premise of his books was to be more flexible, more affectionate, and to treat children as individuals. In this, he has been blamed for helping create generations of people with the need for instant gratification. His motives and teaching may be commendable. After all, there’s nothing wrong with encouraging parents to be more affectionate or to protect their children from feeling bad about themselves. As a result, parents became fearful they would ruin their children if they allowed them to fail which may have contributed to grade inflation. Parents became advocates for their children, pushing teachers to inflate their children’s grades.

Differences in institutions is another factor. Rojestaczer and Healy’s findings show that some private schools are more generous with their grading, making them appear to be superior than their public counterpart. As a result, certain private schools are more predominantly represented in top medical, law and business schools and why some employers show favor to employing someone from these schools. Herein lies the problem: The “variability in grading” from institution to institution and even between majors. The grading standards and criteria are fluctuating. It appears that continuity in grading needs to be taken into consideration if we ever want to fix grade inflation.

Teachers who want to change the system are also trapped by the trend, as an article put out by Concordia University titled How Grade Inflation Hurts Students points out. Working in a system that is inflated puts pressure on honest teachers to bump a student up to an underserved grade. Evaluations also become an issue. Give a student a bad grade (even if deserved), and they’ll give the teacher a bad evaluation, stigmatizing the teacher as a “harsh grader.” There is an expectation from the student’s that they should always receive a good grade. If a teacher is given a bad evaluation, less students will enroll in that class and the school will judge that instructor as a lousy teacher (2-3). “Grade inflation is a classic collective action problem,” Vikram Mansharamani, author of How an Epidemic of Grade Inflation Made A’s Average, points out, “Even if individual teachers want to fight back, they risk harming students arbitrarily in the process. A single bad grade can set students apart when bad grades are hard to come by” (3). So, unfortunately, grade inflation is backing everyone into a corner. It becomes a vicious cycle, everyone has to hand out good grades or the individual gets screwed. Teachers who want to grade fairly have their hands tied. Students wanting their “earned” grade fear standing out as the worst among the inflated “best.” Mansharamani shares the story of two schools, Wellesley University and Princeton University, who tried to combat grade inflation. In the end, they gave up, stating it caused “unnecessary stress on students” (3). This is how generations are being brought up. People are afraid to work hard and fail. And these are our future leaders we’re talking about!

Are We Helping or Hurting Our Students?

Unfortunately, inflating grades is not showing students any favors. Failure is a part of life that helps us become better. If we don’t learn how to fail, we won’t learn how to achieve. Kay suggests that in order to face one's shortcomings, one needs to first identify those shortcomings. And in order to identify those shortcomings, we have to recognize that we can fail (42). How are students to identify areas they need to improve if nobody tells them they need improvement? Constructive criticism isn’t bad. There is a mentality, among millennials in particular, that everyone's a winner. Trophies are handed out just for participation. The elite are no longer awarded for their exceptional performance. We don’t want to hurt the feelings of losers so in turn, we denigrate winners by awarding everyone. Even saying “losers” in the previous sentence makes me cringe because of the P.C. culture in which I live. Our youths are being set up for a very rude awakening when they go out into the real world. Kay sums it up nicely: “To be truly egalitarian, we must admit to ourselves that equality of opportunity isn’t the same as equality of achievement” (43).

When the bar is lowered, the message we send to students is that they are incapable of doing better. We don’t believe students can handle hard work, discipline, and the rigors that come with academia. If given the opportunity to prove they are fully capable, the sky's the limit on where they could go in life. Do we want to make students feel good about themselves? Then we need to let them discover their full potential. This can only happen by letting them fail. Take for instance a child learning to walk. They take a couple steps and fall. Sure, the child may cry, maybe even stop trying for awhile. But then they remember those steps they took and how good they felt, they will try again, and with more success. The excitement and joy supercede that painful failure and gives the child drive to continue working on the newly learned skill. Now, had the child's parents picked them up and said, “You failed, better not try again,” we would say that’s absurd! That’s not helping the child succeed. The parent inadvertently sends a message that they don’t believe their child can achieve. In regards to lowering our standards for students, Kay calls this “...an intolerably pessimistic form of condescension” (43). I agree, but sadly students don’t recognize this, nor do many parents and teachers. Instead, we need to send a message that we do believe in students, that failing isn’t the end, it’s just an opportunity to do better.

So What?

Some people may argue that grade inflation isn’t a big deal. Employers don’t look at grades. There are schools, such as Yale’s medical school and Hampshire College, that don’t even use grading and are doing just fine keeping students motivated (Mansharamani 4). So what’s the big deal? Grades play an important role in many students lives and need to be taken into consideration before abolishing them altogether. A well deserved A brings validation, encouragement, and motivation. Taking that away could be critical to a student’s well being. From an institutional standpoint, grade inflation serves the purpose of bringing in more students, which equates to more dollars. For instance, a person going to college getting poor grades may look at his situation and come to the conclusion that college isn’t the best choice, maybe a trade school would be better, and end up leaving the institution. On the other hand, with grade inflation, this student receives higher grades and comes to the conclusion that college is a perfect fit, thus staying at the institution. The illusion of this person’s abilities, ironically, is setting them up for failure.

As we continue on, looking to the future, we need to keep in the forefront of our minds the value and meaning we want grades to hold. Don’t cheapen the A by handing it out like a piece of candy. Let’s instill in future generations what hard work can earn them. Let’s teach them to be a generation of truth and let them see that they are truly capable.

Author- Tami Miller

"How Grade Inflation Hurts Students." Concordia University Portland Online. N.p., 9 Oct. 2012. Web. 11 Mar. 2017.

Kay, Magdelena. "A New Course." The American Scholar: A New Course - Magdalena Kay. N.p., 2013. Web. 11 Mar. 2017.

Mansharamani, Vikram. "Column: How an epidemic of grade inflation made A’s average." PBS. Public Broadcasting Service, 22 June 2016. Web. 11 Mar. 2017.

Rojstaczer, Stuart, and Christopher Healy. "Grading in American Colleges and Universities." Www.gradeinflation.com/tcr2010grading.pdf. Teachers College Record, 4 Mar. 2010. Web. 11 Mar. 2017.

Christie Hunter is registered clinical counselor in British Columbia and co-founder of Theravive. She is a certified management accountant. She has a masters of arts in counseling psychology from Liberty University with specialty in marriage and family and a post-graduate specialty in trauma resolution. In 2007 she started Theravive with her husband in order to help make mental health care easily attainable and nonthreatening. She has a passion for gifted children and their education. You can reach Christie at 360-350-8627 or write her at christie - at - theravive.com.